Post-Growth Planning

We introduce this issue at a critical time, not only for readers of Built Environment, but in our relationship with the earth systems that support the form of life we have developed on this planet. As the empirical evidence that our current form of growth is incompatible with attempts to live within planetary boundaries builds, so too do the questions about what we do with that knowledge. Debates on how to produce a more equitable, convivial, and sustainable built environment have often sought to direct economic growth or to ameliorate its negative consequences. In contrast the papers in this special issue go to the heart of the matter. They engage with the question of whether growth itself is the problem and if so, then how should the built environment be governed, managed and produced? Thus, we introduce readers to what is a fast-growing body of literature that engages with this question. However, before concluding this introduction with an outline of the individual contributions, we draw out two themes within the debates on the normative response to the evidence that growth is pushing us beyond planetary boundaries and, that cut across the papers. These are critical not only to the debates on economic growth but more importantly to the role it plays in the built environment. First, there is the significance of institutions. Given the way institutions generate the critical path dependencies that have set us on the current trajectory, we introduce readers to debates around the institutional transformations required by the situation we face. Second, we show how the knowledge generated within both the professions and academia will be central to this project.

The academic and policy-oriented research on which the papers in this issue draw traces its origins to the Limits to Growth report (Meadows et al., 1972). In short, we highlight the critique of the still dominant assumption that economic growth can be pursued indefinitely. Yet, the demands this assumption places on finite resources and the pollution it generates are deeply flawed. The scenarios identified in Limits to Growth have proved to be reliable projections for the way patterns of resource consumption and pollution (most obviously greenhouse gases) have developed (Jackson and Webster, 2018). More alarming, as Jackson and Webster point out, are the areas where the predictions proved overly optimistic. The most recent review of the evidence tells us that – due to human activity – six out of nine earth systems on which the current geological era depends have passed the ‘planetary boundaries’ on which continued stability depends (Richardson et al., 2023). This era, known as the Holocene, has given humanity the chance to develop cities and large, complex societies. Knowledge from earth systems science adds further uncertainty to an already risky future with the evidence that the climate system, as with other earth systems, is particularly prone to ‘tipping points’ beyond which stability cannot be assumed at over 1.5 degrees of warming (McKay et al., 2022).

What makes this issue so timely is the way literature critical of growth has recently been reinvigorated by a strand of thought and activism more overtly focused on an assessment of the structural conditions of growth. Known as degrowth, this sees direct calls for a reduction in economic activity, particularly in the Global North, due to its relationship with the emission of greenhouse gases, continued consumption and, often, expropriation of resources (Hickel, 2021; Savini, 2024a; Schmelzer et al., 2022). A recent systematic review of over 950 articles in this field shows how this body of knowledge is expanding and maturing but it also identifies deficits (Engler et al., 2024). In bringing this literature to the readership of Built Environment, we are moving into a field where the sort of policy proposals that Engler and colleagues argue are currently missing can begin to be developed. The most clearly formulated of these comes from Pagani and colleagues’ analysis of the response of policymakers and what might follow if a new post-growth policy goal is adopted (Pagani et al., 2025). Furthermore, a number of the authors, Cerrada Morato, Marjanović and colleagues, Natarajan, and Rydin, suggest that current planning policies need to be broader in scope. They argue that there is a need to embrace the full spectrum of economic activities, foster social capital by protecting and providing social infrastructure, alongside and, in some cases, as an alternative to traditional approaches to the built environment (Cerrada, 2025; Marjanović et al., 2025; Natajaran, 2015; Rydin, 2025).

While the expansion of the literature critical of economic growth, as it is currently conceived, is a reason in itself to introduce the work of our authors in this issue, the trepidation we also feel stems from a need to differentiate ourselves from other recent contributions that reflect the development of this body of literature. Our brief analysis reveals twenty-one special issues covering what we would broadly term (following Crisp et al., 2024) ‘growth critical’ research (for a list of some of those issues see https://timotheeparrique.com/dissertations; see also Banerjee et al., 2021; Johnsen et al., 2017; Rätzer et al., 2018). Kaika and colleagues (2003) offer a review of a section of the literature relevant to the built environment alongside setting out an agenda for research and action with which we have much agreement. In particular we draw attention to their calls for engagement with the existing institutions governing the built environment. Bringing organizational studies literature (Banerjee et al., 2021; Johnsen et al., 2017; Rätzer et al., 2018) into our analysis of special issues in the field draws further attention to the centrality of the institutional question. Furthermore, it brings in literature where the term ‘post-growth’ is dominant. As Crisp et al. (2004) show, a broader definition of perspectives critical of the way economic growth is defined reveals a far greater adoption of actual policies in this area. This must be tempered by the criticism that the adopted policies that acknowledge, albeit in a limited way, a critique of growth are often the least transformative ones.

Thus a brief discussion of terminology is necessary to orientate the reader and introduce the differing use of the terms ‘post-growth’ and ‘degrowth’ by the authors in this issue. We have elected to use the more open ‘post-growth’ as the overarching term. Nonetheless, that the authors use of both terms reflects the breadth of the debate encompassed by the papers. Within this growing body of research and thought there remains a lack of agreement on the boundaries between the two terms and even what they mean. Marjanović and colleagues’ distinction between post-growth as the objective and degrowth as one path by which it might be reached may offer a helpful heuristic (Marjanović et al., 2025). Yet this is simply a single point in a vital and ongoing debate on the nature, sufficiency, and effectiveness of the political project implied by a critique of growth and, crucially, the role that built environment professionals and researchers should play in it (see Rydin, 2024; Savini, 2024a, 2024b). As academics, we are predisposed to definitional clarity, and we acknowledge that, for some, the interchangeable use of different terminology may be frustrating. Our view on this is first that it preserves what we believe is a productive ambiguity in a debate that is ongoing and one that is not only conducted within academia. This ambiguity is worth preserving for a while. Given the different audiences that built environment professionals and academics speak to, the avoidance of explicitly normative analysis can be a valid strategic choice (Olson and Sayer, 2009). This is important because for many the evidence that the pursuit of growth is a risky strategy may prove more palatable than claims we should plan to reduce it. However, it should not be inferred from this that there is more that separates different strands of this debate than connects them. Thus, we return to the fact that the crucial point of agreement is ultimately an empirical one. It is hard to overstate the significance that, at this critical juncture, there is no evidence that economic growth is compatible with even relatively conservative international agreement, let alone the science of planetary boundaries and their tipping points. Growth cannot be decoupled from resource depletion and greenhouse gas emissions (Haberl et al., 2017; Vadén et al., 2020; Vogel and Hickel, 2023).

While the evidence on decoupling is empirical, the project of responding to it while retaining equitable outcomes within the built environment must be acknowledged as a normative one. Although we believe the alternatives of failing to respond are unappealing, we must acknowledge a realpolitik in which economic growth is firmly embedded. This makes political action to actively reduce growth making policy a hard sell. Harder still is the idea in some of the degrowth literature that growth must be constrained in some countries in order to permit development in the Global South. The uneven distribution of the benefits of growth within nations means that without a deeper analysis of its suitability for the task, it remains the only mechanism for addressing the situation whereby some groups, regions, and areas are worse off than others. Closely connected to this is the way that much of the governance of the built environment, particularly through practices like planning, is relatively local. Given the uncertainty as to the extent, seriousness and ultimately efficacy of action at the national and international scale, it is legitimate for local-level actors to question why they should forgo imperfect but familiar tools for resolving issues they face.

Yet, as we demonstrate, planning in particular has a lot to offer in this respect. First, we would point to the origins and evolution of planning. Among the multiple strands that constitute contemporary planning it is possible to trace a number – the promotion of public health, conservation and environmental protection, equitable place-making, and the empowerment of communities – that at the very least ameliorate the impacts of growth if not implicitly challenging assumptions it is the only mechanism by which social progress is achieved. More recent iterations in the form of strategic and regional planning are seen by some as a clear challenge to the consequences of unrestrained growth (Savini, 2024b). Thus, it would appear that while the current centrality of growth as a vehicle by which planning shapes the built environment is problematic it need not always be so. Indeed, many of the tools planning has developed will undoubtedly be useful under post-growth scenarios (Durrant et al., 2023). Second, we point to the increasing acknowledgement of the role of institutions within the field of planning. Rather than considering planners as purely rational actors making intentional and value-free decisions, new institutionalism views them as influenced by historically and culturally ingrained values and beliefs that shape their actions and choices (Taylor, 2013). Therefore, analysing institutions offers insight into why certain planning contexts resist change and why some development paths fail to materialize (Hall and Taylor, 1996). It also allows for the exploration of necessary changes to envision new spatial development directions.

The institutional perspective is critical in understanding the process of creating post-growth societies as this requires a deliberate restructuring of the economic, political, and social institutions linked to capital accumulation. This is necessary to ensure fair, sustainable, and dignified survival for both human and nonhuman species over time and space (Schmid, 2019). Such restructuring involves developing and implementing new institutional frameworks, planning tools, and practices, encompassing formal and informal aspects, to facilitate the shift to post-growth futures. However, it is unlikely that these institutions could emerge solely through rational design, central control, or entirely independently of existing societal norms and practices. According to a historical institutionalist perspective, post-growth institutions will develop gradually and adaptively as actors recognize the coordination failures of the capitalist institutions that have proved incapable of decoupling growth from its ecological consequences and seek to both alter their path-dependent trajectories and to develop and nurture alternative institutional arrangements.

The practice of planning is unique in that it tries to span different social systems (Van Assche and Verschraegen, 2008; Lamker and Marjanović, 2022). This means that planning is not only influenced by various institutional and societal norms, but it also has the ability to transform those norms. Therefore, planning is in a special position to engage directly with instances of institutional failure and inspire the envisioning and pursuit of post-growth alternatives. The contributions to this issue demonstrate that such instances are not uncommon, and planners (and other actors) are not completely unaware of them. These situations can occur in various localities, including shrinking cities and urbanized peripheries, and across different social provision systems and elements of physical and social infrastructure, like housing, water supply, education, and the law.

Opportunities for change arise when different actors coalesce around an issue for which coordination failure is recognized, and they seek to develop alternative coordination mechanisms. Whether this alternative will embody post-growth rationale and, if so, whether it will succeed in materializing through concrete solutions remains uncertain. However, the examples provided indicate that post-growth considerations are not entirely inconceivable within dominant institutional arrangements and can sometimes even be facilitated by existing mechanisms. For instance, while representatives from selected London housing authorities became receptive to post-growth alternatives only after Pagani and colleagues (2025) introduced a quote by Meadows (1999) during their focus group discussion, the development of non-commercial investment collectives around schools in London was significantly driven by the government-initiated School Superzones project, as demonstrated by Natarajan (2025). Similarly, Walton illustrates how elements of post-growth thinking permeate formal decision-making at various levels, sometimes failing to actualize concrete decisions while, in other instances, gaining significant leverage in planning deliberations (Walton, 2025).

Building on these insights, we can theorize that planning must recognize and engage with institutional failures within the capitalist system of accumulation to catalyse the post-growth transition. These situations represent opportunities for developing post-growth institutional alternatives or supporting post-growth initiatives that have already emerged but struggle to gain traction. To achieve that, planners require new forms of knowledge and expertise, including accounting for diverse economies often overlooked in conventional planning activities, as argued by Rydin (2025), or a deeper appreciation for the institutional characteristics of a given context, as underscored by Cerrada Morato (2025). The collected views suggest that this knowledge should not only be embedded in institutional decision-making, as demonstrated in Walton’s paper (2025), but must also be actively mobilized in an empowering and emancipatory manner. This entails catalysing the creation of new partnerships and modes of cooperation, as demonstrated by Marjanović and colleagues (2025) and Natarajan (2025), as well as stimulating altruistic perspectives, as argued by Gabrieli (2025). In other words, to facilitate the transition to a post-growth future, planning must embrace new knowledges and use them to drive institutional change by encouraging novel partnerships around emblematic issues of institutional failure, empowering actors to cooperate beyond selfish reasons.

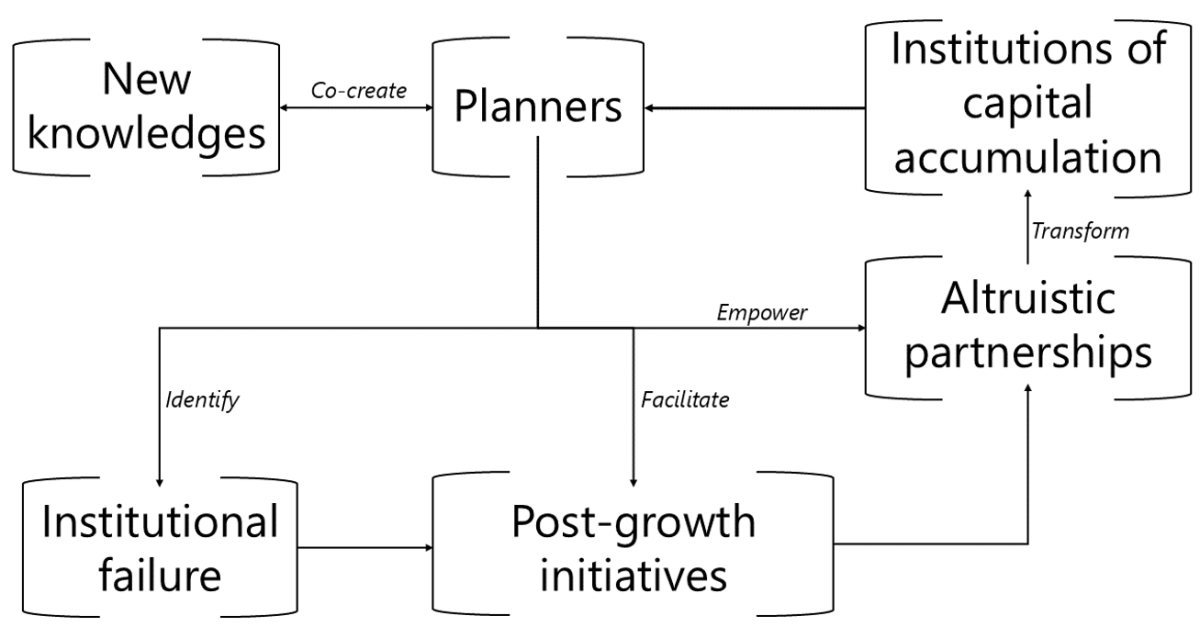

Counter-hegemonic projects certainly need alliances between civil society and state action through planning in order to transform the latter (Savini, 3024b). Yet what is missing in this perspective is the role in transforming existing institutions. Thus, we view the process as one of both altering the social and ecological path dependencies of those institutions for which this is possible; we have to be clear here that the institutions that cannot transform will require a regulative solution and the fostering of the sort of initiatives and partnerships that generate new institutional arrangements required for post-growth societies to survive and thrive (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

We have sought to capture the role of planning in relation to existing institutions in moving us along the path to a post-growth future. We see planners as centrally involved in identifying existing examples of institutional failure and path dependencies heading in the wrong direction. They are also able to facilitate existing examples of post-growth initiatives, concrete examples that prefigure an alternative future. These initiatives can foster altruistic partnerships based on a different and wider rationale than market-oriented self-interest, and here also planners can play a role by empowering these new partnerships. This has the potential to create new institutional arrangements and (eventually) transform existing institutions of capital accumulation. But, as the figure illustrates, to do this we need new knowledges and planners can be centrally involved in creating the knowledge that will support all the other linkages that are identified in the diagram.

We now turn to the second theme explored in this issue. The question of knowledge production within the normative projects of planning for the shift to a post-growth future. Research informed by a future-oriented normative project in an inherently uncertain context brings certain difficulties. Establishing facts that either do not or may not exist yet is inherently problematic. More pressing, though, is the way existing institutional facts simply identify the pathways that need to be altered if the destinations the evidence suggests they lead towards are to be avoided. In themselves, they do not bring about the necessary change. The two sources of knowledge the post-growth and degrowth literature draw on both provide different ways of addressing the issue. For the research drawing on the methods and approach of the Limits to Growth, we see the construction of models at a larger scale, be that of multiple earth systems, the climate, material flows or social systems. Part of the function is predictive in the loosest sense as the level of precision runs across a spectrum from the broad direction of travel identified in earlier studies through to contemporary advances in the capacity to integrate climate models and weather data in order to identify extreme weather events. This knowledge certainly informs the context in which decisions are made. Here, the models intrude into the present in the form of rapidly changing weather patterns that challenge fundamental assumptions about the way the built environment will function.

In contrast, much is made in the literature, particularly from a degrowth stance, of the importance of prefiguration. The identification of performative instances and experiments that show what a future without growth might look like provide real-world, present-day examples of a possible future (Meissner, 2021). While we see this as a vital part of generating knowledge on the feasibility of alternatives, it brings with it a tendency to focus on the small scale of the ‘innovative models of “local living” … cooperative property and cooperative firms’ (Kallis et al., 2012, cited in Meissner, 2021, p. 513). In one sense, this is inevitable, given the role played by niches or gaps left by the institutions of growth and capital accumulation (Cerrada Morato, 2025). While we are not the first to point out that this is a potential limitation of this approach (Kallis and March, 2015), we also acknowledge that it is a vital component in generating the knowledge necessary for a broader societal shift. The problem comes when this is the only strand. First, it may place unfounded weight on the capacity or desire of such post-growth initiatives to scale up. No doubt, some will, and some may scale out through self-replication. Others, however, may prove to be a product of a distinct set of circumstances. While they may be appropriate to function quite effectively within a niche, there is no guarantee that they will function in the same way at a different scale or even that the actors upon which the initiatives depend have the desire to do so.

A second limitation is that the evidence prefigurative examples offer is somewhat skewed towards those who already accept the premise of a need to shift away from current forms of economic growth. To become viable pathways, they must also compete with what is currently on offer to most people. Global supply chains configured around instantaneous, wide-ranging and low-cost choices for consumers, mobility and information infrastructures predicated on unattenuated flows often combined with subsidy for the most polluting manifestation of this and a political culture in which the demands of citizenship are minimal shape the worlds which the vast majority of people inhabit. The success of the utilitarian logic to which the institutions that constitute this world adhere has been to ensure that the dis-benefits are either diffuse or deferred (globally or to future generations), meaning that current institutional frameworks offer a considerable barrier even to conceiving of, let alone realising alternatives.

Yet, as Pagani and colleagues (2025) show, modelling the existing institutional framework can make a start in identifying the failings. Showing how a system functions or fails to do so can also be diagnostic spotting opportunities for different institutional pathways. However, if such diagnoses are conducted in the absence of a broader normative frame, then there is a danger that the diagnosis remains confined to an analysis of the ability only to achieve objectives determined within existing institutional frameworks. All the authors that analyse existing institutions – the law, water infrastructure, education, local economies, housing and those generated by shrinking cities – share this normative project. The diagnosis is of the ability for either reconfiguration towards or support of the objective of moving beyond growth as a determinant or driver. While this provides an external framework against which to measure it is one we feel needs further development. Given the nature of such a project and our role within it, we restrict ourselves to the question of knowledge generation.

First, it is vital to be clear that knowledge derived from normative reasoning of the type we have sought to develop cannot alone alter reality. It is, however, necessary in understanding what form a different world might take (Olson and Sayer, 2009). Furthermore, as part of a bigger project we would argue that it does have a vital role to play in the type of cultural shifts that are a prerequisite of any change to the status quo. Olsen and Sayer examine the capabilities approach of Martha Nussbaum and Amartya Sen as one potential framework. In this issue, Gabrielli (2025) explores Buen Vivir (another perspective on the ‘good life’) with other authors (Griggs and Howarth, 2023; Meissner, 2021; Savini, 2024b) citing Kate Soper’s ‘alternative hedonism’ as a way of approaching what a world beyond growth might look like (Soper, 2020). Yet, it is through disciplines such as planning, which, after all, has always set out normative visions of a planned future, through which such knowledge can be channelled. This has the advantage of not only the capacity to foster those prefigurative initiatives that may have a role to play at different scales but also by exposing the gaps in existing frameworks through which cultural changes can exert an influence and identifying institutions that are inconsistent with evolving norms. Thus, the process of demonstrating that change is necessary and possible becomes an iterative one. The history of success and failure in reconfiguring the built environment and aligning local needs with the global forces that shape it gives it a vital role in responding to pressures generated at a different scale to which they can be governed as well as also in learning from the experience of doing so.

Finally, we consider the specific knowledge contained in the papers that make up this special issue. While the debate and terminology may be new to some, the features of the built environment viewed through the lens of post-growth are those key to the readership of this journal. Suburban development and housing have both been considered in some depth in previous issues, as have shrinking cities. Other features, such as the role of local economies and schools, are likewise familiar elements of the built environment, like the others, viewed in this issue through the lens of post-growth. Built Environment’s cross-disciplinary ethos offers a unique vantage point from which to view some of the current debates surrounding economic growth. Thus, we have sought contributions from areas like planning law and economic theory, which we believe widen the scope of this issue and introduce new perspectives. Thus, the papers both directly address the implications of a post-growth agenda for planning and suggest an expanded role for planning authorities and planners, as well as exploring broader legal and economic aspects from a post-growth perspective. Atop our emphasis on the role of knowledge production, the institutional dimension enables us to understand how current norms and routines of practice may hinder planning for post-growth. Yet the authors here also suggest pathways for institutional reform to enable post-growth planning.

For example, Walton’s examination of English and Welsh planning law highlights the way that legal institutions – as operationalized through the actions of planners, planning inspectors, and judges – act as crucial gatekeepers for urban development (Walton, 2025). As such, they can help to determine whether forms of development that are necessary for a post-growth future – such as low-carbon options – are blocked or enabled. In one case he examined, the potentially low carbon option of refurbishment was rejected, while in the other, carbon assessment became a key factor in the final planning decision. He argues for the importance of embedding carbon assessments in planning decision-making and of having clear guidance on the form that these assessments should take.

Several of the papers highlight the core processes of planning institutions in promoting governance networks as a means to deliver post-growth options. In her study of water infrastructure in the suburbs of Santiago di Compostela, Spain, Cerrada Morata (2025) emphasizes the need for ‘messy’ planning that will work across actors, scales, and dimensions and, thereby, promote niches for experimentation. These forms of planning by governance also need to take into account the specific institutional characteristics of place, in her case of suburban areas.

Marjanovic and colleagues (2025) also stress the need for novel partnerships and experimentation to develop post-growth pathways within planning and thereby subvert the norms of growth-dependence. They develop these conclusions from studying planning for shrinking cities in various geographical locations, where planning for growth is not a possibility, arguing that these cities have lessons for post-growth futures elsewhere.

However, many of these papers also emphasize that such changes in planning practices can only contribute to post-growth futures where there is also a shift in policy agendas and, further, in social values more broadly across communities and societies. Cerrada Morato (2025) points to the requirement for a broader consensus on the necessity of a post-growth future to drive new governance arrangements in local planning. While Marjanovic and colleagues (2025) see the articulation of post-growth ideas as opening up possibilities for new policy aims.

Pagani and colleagues (2025) provide an interesting thought experiment of what might follow if a new post-growth policy goal is adopted. They consider the implications of implementing a new build moratorium for social housing in London. Using a methodology that combines systems mapping and stakeholder workshops, they are able to identify a number of more specific institutional barriers that might impact this new policy tool. They argue that these barriers might actually prompt innovation, notably in business models, but again they also emphasize that the tool of the moratorium itself has an impact in challenging dominant narratives. This is particularly a challenge to existing institutional knowledge that building new is building better and raises the possibility of narratives of sufficiency and finity instead.

The idea of challenging and changing social values more generally is raised by Natarajan (2025). She looks in detail at the new policy initiative of Super School Zones in London, which focuses on developing the social networks around schools with the aim of improving community wellbeing. These create new practices, build new forms of social capital, and create new coalitions of actors. All of these have the potential to embed post-growth values within local communities and Natarajan sees an expanded role for planning in supporting such initiatives.

Gabrielli (2025) addresses the thorny question of whether the values at the heart of economics have to be aligned for growth, using theoretical investigation based on game theory. Instead, he sees the potential for altruism to frame a new form of economics. This raises the question of how the ‘economy’ is defined, which Rydin (2025) also addresses. She sees the potential of utilizing under-emphasized elements of diverse economies, such as small local firms and social enterprises, as a way of prefiguring a post-growth future. She investigates the conditions for survival and longevity using a variety of European examples. From this, she draws out the knowledges that planning for such a future would require.

Taken together the papers all accept the framing of growth as a problem, they do not however deny researchers and practitioners avenues through which to negotiate solutions to the challenges thrown up by the built environment. They show how disconnecting from the motor of growth need not be taken to imply reorientation towards some utopian fantasy world free from the complexities of modern societies, far from it. Many of the familiar forms are likely to persist from the law to education and economic activities. Physical forms like suburban development will continue to exist and populations will rise and fall leaving behind urban areas where government and governance must respond. To be clear, planning without growth poses challenges. We have to acknowledge one of the greatest of these is the political acceptability of any project in which explicitly post-growth planning could form a part. Yet such uncertainty is tiny in comparison to the uncertainty generated by the pursuit of growth in its current form. Any reorientation away from the pursuit of economic growth, either by choice or necessity, will clearly be driven by factors beyond the built environment. Yet these factors will be played out within it. Thus, it is the questions of how these processes are shaped, that the authors in this special issue have begun to offer timely and necessary answers.

REFEREENCES

- Banerjee, S.B., Jermier, J.M., Peredo, A.M., Perey, R. and Reichel, A. (2021) Theoretical perspectives on organizations and organizing in a post-growth era. Organization, 28(3), pp. 337–357. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508420973629.

- Cerrada Morato, L. (2025) Learning from an ordinary suburban post-growth struggle: not by design, nor by disaster. Built Environment, 51(1), pp. 50–72.

- Crisp, R., Waite, D., Green, A., Hughes, C., Lupton, R., MacKinnon, D. and Pike, A. (2024) ‘Beyond GDP’ in cities: assessing alternative approaches to urban economic development. Urban Studies, 61(7), pp. 1209–1229. https://doi.org/10.1177/00420980231187884.

- Durrant, D., Lamker, C. and Rydin, Y. (2023) The potential of post-growth planning: re-tooling the planning profession for moving beyond crowth. Planning Theory and Practice, 24(2), pp. 287–295. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2023.2198876.

- Engler, J.O., Kretschmer, M.F., Rathgens, J., Ament, J.A., Huth, T. and Von Wehrden, H. (2024) 15 years of degrowth research: a systematic review. Ecological Economics, 218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2023.108101.

- Gabrieli, T. (2025) Economics of post-growth planning: cooperation and altruism. Built Environment, 51(1), pp. 35–49.

- Griggs, S. and Howarth, D. (2023) Contesting Aviation Expansion; Depoliticisation, Technologies of Government and Post-Aviation Futures. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Haberl, H., Wiedenhofer, D., Erb, K.-H., Görg, C. and Krausmann, F. (2017) The material stock–flow–service nexus: a new approach for tackling the decoupling conundrum. Sustainability, 9(7), 1049. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9071049.

- Hall, P. and Taylor, R. (1996). Political science and the three new institutionalisms. Political Studies, 44(5), pp. 936–957.

- Hickel, J. (2021) Less is More: How Degrowth Will Save the World. London: Penguin.

- Jackson, T. and Webster, R. (2018) Limits to Growth revisited, in Deeming, C. and Smyth, P. (eds.) Reframing Global Social Policy: Social Investment for Sustainable and Inclusive Growth. Bristol: Bristol University Press, pp. 295–322.

- Johnsen, C.G., Nelund, M., Olaison, L. and Meier Sørensen, B. (2017) Organizing for the post-growth economy. Ephemera, 17(1), pp. 1–21. Available at: http://www.ephemerajournal.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/contribution/17-....

- Kaika, M., Varvarousis, A., Demaria, F. and March, H. (2023). Urbanizing degrowth: five steps towards a radical spatial degrowth agenda for planning in the face of climate emergency. Urban Studies, 60(7), pp. 1191–1211. https://doi.org/10.1177/00420980231162234.

- Kallis, G. and March, H. (2015). Imaginaries of hope: the utopianism of degrowth. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 105(2), pp. 360–368. https://doi.org/10.1080/00045608.2014.973803.

- Kallis, G., Kerschner, C. and Martinez-Alier, J. (2012) The economics of degrowth. Ecological Economics, 84, pp. 172–180.

- Lamker, C. and Marjanović, M. (2022) Reproduction of spatial planning roles: navigating the multiplicity of planning. plaNext–Next Generation Planning, 12. https://doi.org/10.24306/plnxt/82.

- McKay, D.I.A., Staal, A., Abrams, J. F., Winkelmann, R., Sakschewski, B., Loriani, S., Fetzer, I., Cornell, S.E., Rockström, J. and Lenton, T.M. (2022) Exceeding 1.5°C global warming could trigger multiple climate tipping points. Science, 377(6611). https://doi.org/10.1126/SCIENCE.ABN7950.

- Marjanović, M., Durrant, D. and Thompson, M. (2025) Planning for degrowth: insights from shrinking cities. Built Environment, 51(1), pp. 16–34.

- Meadows, D.H. (1999) Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System. Hartland, VT: The Sustainability Institute.

- Meadows, D.H., Meadows, D.L., Randers, J. and Behrens, W. (1972) The Limits to Growth: A Report for the Club of Rome’s Project on the Predicament of Mankind. New York: Universe Books.

- Meissner, M. (2021) Towards a cultural politics of degrowth: prefiguration, popularization and pressure. Journal of Political Ecology, 28, pp. 511–523.

- Natarajan, L. (2025) Social infrastructures for post-growth value generation: school-based initiatives in London. Built Environment, 51(1), pp. 113–131.

- Olson, E. and Sayer, A. (2009) Radical geography and its critical standpoints: embracing the normative. Antipode, 41(1), pp. 180–198. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8330.2008.00661.x.

- Pangani, A., Macmillan, A., Savini, F., Davies, M. and Zimmermann, N. (2025) What if there were a moratorium on new housebuilding? An exploratory study with London-based housing associations. Built Environment, 51(1), pp. 73–94.

- Rätzer, M., Hartz, R. and Winkler, I. (2018) Editorial: post-growth organizations. Management Revue, 29(3), pp. 193–205. https://doi.org/10.5771/0935-9915-2018-3-193.

- Richardson, K., Steffen, W., Lucht, W., Bendtsen, J., Cornell, S.E., Donges, J.F., Drüke, M., Fetzer, I., Bala, G., Von Bloh, W., Feulner, G., Fiedler, S., Gerten, D., Gleeson, T., Hofmann, M., Huiskamp, W., Kummu, M., Mohan, C., Nogués-Bravo, D., … Rockström, J. (2023) Earth beyond six of nine planetary boundaries. Science Advances, 9(37). https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adh24.

- Rydin, Y. (2024) A postgrowth response to Savini’s degrowth vision. Planning Theory. https://doi.org/10.1177/14730952241278055.

- Rydin, Y. (2025) Challenging pro-growth dynamics by developing planning knowledges for diverse economies. Built Environment, 51(1), pp. 95–112.

- Savini, F. (2024a) Degrowth, legitimacy, and the foundational economy: a response to Rydin. Planning Theory. https://doi.org/10.1177/14730952241278056.

- Savini, F. (2024b) Strategic planning for degrowth: what, who, how. Planning Theory. https://doi.org/10.1177/14730952241258693

- Schmelzer, M., Vetter, A. and Vansintjan, A. (2022) The Future is Degrowth: A Guide to a World beyond Capitalism. London: Verso.

- Schmid, B. (2019) Degrowth and postcapitalism: transformative geographies beyond accumulation and growth. Geography Compass, 13(11), e12470.

- Soper, K. (2020) Post-Growth Living: For an Alternative Hedonism. London: Verso.

- Taylor, Z. (2013) Rethinking planning culture: a new institutionalist approach. Town Planning Review, 84(6), pp. 683–702.

- Vadén, T., Lähde, V., Majava, A., Järvensivu, P., Toivanen, T., Hakala, E. and Eronen, J.T. (2020) Decoupling for ecological sustainability: a categorisation and review of research literature. Environmental Science and Policy, 112, pp. 236–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ENVSCI.2020.06.016.

- Van Assche, K. and Verschraegen, G. (2008) The limits of planning: Niklas Luhmann’s systems theory and the analysis of planning and planning ambitions. Planning Theory, 7(3), pp. 263–283.

- Vogel, J. and Hickel, J. (2023) Is green growth happening? An empirical analysis of achieved versus Paris-compliant CO2–GDP decoupling in high-income countries. The Lancet Planetary Health, 7(9), pp. e759–e769. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(23)00174-2.

- Walton, W. (2025) Can zero-carbon development be delivered through the existing English legal and policy planning framework? Built Environment, 51(1), pp. 132–146.